What’s in a name?

These days, Paris bags first dibs on the handle ‘The City of Light’.

Accepted wisdom suggests this emerged from the French capital’s prominent role in the age of enlightenment. However, Paree’s lofty claim to La Ville Lumière title actually comes from something much more mundane.

It is based on the city’s innovative attempts to combat crime.

In the mid-17th century, following a period of unrest, King Louis XIV pledged to restore law and order. As part of The Sun King’s purge, Paris’ chief of police placed lanterns on the streets and urged residents to light their windows with candles and oil lamps. Lighting deterred criminals from lurking in dark alleys.

Then, a few centuries later, in 1829, Paris lauded itself as one of Europe’s first cities to roll out gas street lighting.

Yet, Paris doesn’t have a monopoly on claims to this City of Light business.

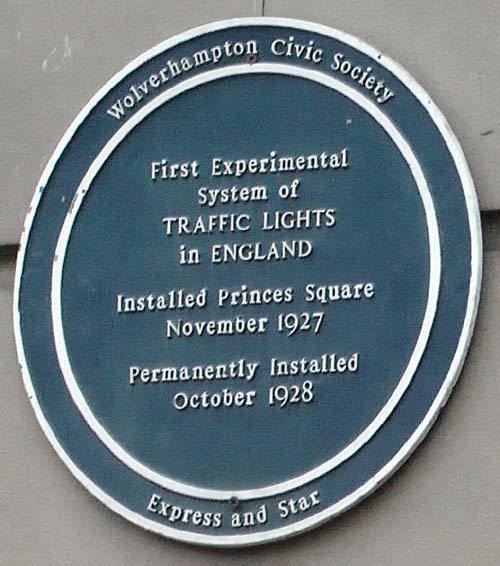

In the interests of fairness, I would like to point out that Wolverhampton, an industrial town in the West Midlands, is Britain’s City of Light. Gas illuminated Wolverhampton in 1821, eight years earlier than Paris, and they erected a forty-foot gas-light pillar to celebrate. In 1927, the town’s Prince’s Square was home to England’s first set of automatic traffic lights.

Image courtesy of McDarke, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A few other unlikely places around the globe also claim City of Light status, too.

For example, New Bedford, Massachusetts lubricated the wheels of industry and lit the world with its whale oil. In 1847, the city seal inscribed the motto Lucem Diffundo (I Spread Light).

Eindhoven in the Netherlands makes matches and is home to light bulb manufacturer Philips.

QED.

Yet Wolverhampton, Paris, Eindhoven, and New Bedford, Massachusetts, are all mere pretenders to the title. The first written record of the town of Ohrid in North Macedonia refers to Lychnidos, literally The City of Light. And that was in 209 BC.

The reasons are unclear. On the shore of a four-million-year-old lake with the same name, Ohrid’s natural light certainly has a special ethereal quality. But like Paris, perhaps the title is also connected with enlightenment.

Ohrid was a cultural and religious centre way back in antiquity.

In the 1600s. Ottoman traveller, Evliya Çelebi, reported 365 chapels within the town boundaries: one for every day of the year. Although there are fewer nowadays, this netted Ohrid another title: ‘The Jerusalem of the Balkans’. Its university dates to the 9th century, and is reputedly the oldest in Europe.

Archaeologists found 5,000-year-old artefacts from Europe’s earliest settlements. Ohrid boasts a 2,000-year-old amphitheatre, and is crowned by Samuel’s Fortress, whose origins are linked to Alexander The Great’s father.

The best way to enjoy an ancient town in a sublime location that overflows with character and history is to wander.

Mark, and I walked from our lakeside stopover to the castle with our travel companion, Jean. Jean had hitched a ride over the Albanian border with us and camped next door in what turned out to be a very noisy car park. Unsurprisingly, he decided to upgrade his accommodation and seek refuge in Ohrid’s backpackers’ hostel.

En route, we passed an upturned boat with the magnificent red-and-yellow sunburst that is the Macedonian flag painted on its hull. Miserable Mark was too impatient to let me pose the puppies on it for a photo.

Miserable Mark wouldn’t let me pose he puppies for a photo on the hull of the boat bearing the Macedonian flag!

In the shimmering morning heat, we appreciated the slight shade provided by the thin woodland as the path circled around the hill. Jean was young and fit – he had walked to Albania from Istanbul. Mark and I could almost keep up with him on the ascent, since he was lugging a 30 kg backpack. Even so, he boasted,

“Today, my pack is really light because I don’t need to carry any food or water!”

At the top, a lovely café by the castle gateway provided a welcome rest stop. The waitress brought a free serving of green figs in sugar, a local speciality. I tried Macedonian coffee. It was strong, black, and slightly less gritty than Turkish. It was brewed and served in a tiny copper pan. It was after midday, so Mark tucked into a Macedonian beer, while Jean went for full fortification: Macedonian coffee with a beer chaser.

The café had some quirky décor, including an old motor scooter. When Miserable Mark wasn’t looking, I posed Ruby on the saddle and took a photo.

The history of Ohrid’s castle is a little mysterious. Nothing much is certain, except that the views from the top are very spectacular.

On a hill that rises 100 metres (330 ft) above the lake, the fortress walls are 10 to 16 metres high (33 to 53 ft), and punctuated by eighteen towers. Razed and rebuilt many times, it was ruled by the ancient Macedonians, Romans, Byzantines, Slavs, and Ottoman Turks.

Known as ‘Samuel’s Stronghold’, this is one of the largest medieval fortifications in North Macedonia, although North Macedonia is rather a small country! The current layout allegedly dates from the time of Emperor Samuel (Samuil) of Bulgaria, who reigned from 976 to 1014.

Compatriots described Samuel as ‘invincible in power and unsurpassable in strength’. He made Ohrid the capital of the first Bulgarian Empire and was in constant conflict with the Byzantines.

Contemporary poet, John Kyriotes, likened Samuel to Halley’s comet, which appeared In 989:

“Above the comet scorched the sky, below the Cometopoulos (Samuel) burns the West.”

John Kyriotes Geometres

Yet, the castle’s story predates Samuel by more than a millennium. Around 200 BC, Greek historian, Polybius, wrote that King Philip II of Macedon fortified Lychnidos.

Phil, of course, was Alexander The Great’s dad.

In the early 2000s, the Samuel’s Stronghold underwent extensive archaeological investigation and renovation. They rebuilt its battlements from scratch, while excavations confirmed the existence of an earlier fortress dating to 500 BC. Discoveries included magnificent golden masks and the Macedonian sun, the symbol of Philip II and Alexander of Macedon. These artefacts authenticate Polybius’ record and Ohrid’s connection with the ancient kingdom of Macedonia.

As we drank in the sensational 360-degree panorama from the ramparts, we spotted a beautiful church on a green plateau above the satin blue lake. Framed by a darker green forest, striking geometric patterns in red brick zig zagged across its pale stone walls. Terracotta tiles capped its multi layered clover-leaf confection of roofs, domes, and towers.

We followed the path downhill for a closer look at the Byzantine Church of Saints Clement and Panteleimon. It sits in an archaeological area known as Plaošnik. Inside, the cool echoes of ecclesiastical silence exuded the most wonderful, calming atmosphere.

St. Clement built the church in the 10th century, and dedicated it to St. Panteleimon. I mentioned earlier that Ohrid was an important seat of learning. St. Clement founded the Ohrid Literary School, where he taught the first students of the Galgolitic alphabet. They used the script to translate the Bible into the Old Church Slavonic language.

Nowadays, all Slavic countries have adopted either the Latin or Cyrillic alphabets. A few of the clergy keep the Old Church Slavonic language and its Glagolitic script alive, although Cyrillic purloined a few letters from Galgolithic, so it endures In a small way.

The North Macedonian language uses Cyrillic script.

Finally, in North Macedonia, my childhood obsession with Uri Gagarin and the Russian space race paid off. As a geeky pre-teen, I set out to teach myself Russian. I didn’t get far beyond the basics, like кофе, (kofe) – have a guess! But I learned the alphabet, so at least I could read place names in Cyrillic on road signs.

At the church, Mark repented his earlier puppy shot sins. He actually offered to arrange The Fab Four for a photograph in a stunning Byzantine archway.

However, he still couldn’t help himself, and photo bombed one of my shots.

The treasures of Plaošnik didn’t stop with church.

Next door, we stumbled upon the ruins of the 5th century baptistery. Its breathtaking mosaic floors surround the remains of a central baptismal pool, with steps down into it. The mosaics featured plants, such as grapes and vines, as well as realistic depictions of animals and birds. We were surprised to see swastikas in the intertwining borders.

You may not know that the swastika is an ancient religious emblem. The word actually derives from the Sanskrit, svastika, meaning ‘conducive to well-being’. The right facing swastika represents sun, while the left facing sauvastika represents night.

To Buddhisst, Hindus, and Jains, it symbolises divinity, good luck, and prosperity.

In Indo-European religions, the swastika usually represents the gods of thunder. These include Zeus and Jupiter from Greek and Roman mythology, and the Norse, Saxon, and Germanic hammer-wielding Thor.

In Europe in the early 20th century, swastikas were a widely used symbol of good fortune and happiness. Author Rudyard Kipling was born in British India. Many older editions of his books have a swastika printed on their covers. Until the 1930s, Robert Baden Powell adopted it for his UK scouting movement and Danish brewer, Carlsberg, featured a swastika in its logo.

The swastika only gained universally evil connotations in the West when the German Nazi Party appropriated it as the insignia to represent the Aryan race.

On a hunt for lunch, we continued down cobbled streets into the old town. We passed the Hellenistic amphitheatre, which is so well preserved it is still in use today. Curiously, it survived intact because the locals hated it. In addition to gladiatorial combats, the Romans used it to execute Christians. When the Roman empire collapsed, the townspeople buried it. Like Pompeii, it remained hidden for two millennia, until the 1980s, when it was uncovered accidentally during some building work.

We followed our noses along a boardwalk and happened upon a lakeside restaurant. At Kanevche, we tried some Macedonian specialities: stuffed cabbage leaves, stuffed peppers – and beer. Beer was our only option to cool off. If you remember, in Struga Crypta, Mark wet his pants by diving into the river while waiting for pizza. Here, a sign dictated ‘no swimming’ from the terrace.

Mark and I were too hot and tired to walk back, so we said, “Au revoir,” to Jean and caught a boat taxi from the restaurant.

The leisurely ride across the lake’s languid waters was worth the 10 euro fare for beauty alone. From the water, we saw a different view of Ohrid, and caught a glimpse of the Church of Saints Clement and Panteleimon. When we arrived, the pups didn’t mind getting their paws wet as we leapt from the bow on to the beach.

Our pilot liked The Pawsome Foursome and seemed to enjoy having them in his boat. It prompted Mark to comment,

“I’ve seen more pet dogs in a day in Macedonia than we did in six weeks in Albania!”

Ohrid had charmed us. But, little did we realise that in Macedonian terms, all that City of Light nonsense was peanuts.

In our next destination, Skopje, the capital, we were about to uncover the mother of all naming disputes – and get caught up in the news…

Enjoy Reading? Sharing is Caring!

If you enjoy my blog, why not share it? Or sign up to receive regular email updates automatically – with no spam guaranteed.

Beautiful photos as always! You can never have too many puppy poses!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know! Especially with a national flag.

I shall pass your comment on to Miserable Mark!

LikeLike

#NotBitter 😂

LikeLiked by 1 person

#NotBitterAtAll!

LikeLike

What a beautiful place this appears to be! Loved the history you put into your post too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Anna. It is very gorgeous, and so steeped in history. I’m glad you like my historucal snippets, I find history very fascinating!

Thank you for stooping by to read and comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome Jacqueline, I love history and reading so your posts are always a joy to me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Green figs in a sugar syrup … I never walk past a bottle of that at a farmer’s market! The views from Ohrid’s castle are breathtaking and what a lovely church. The history here is just amazing – like that of The old theatre. It makes me wonder how many places in the world are still buried that we don’t even know about! Ah, I can see how much Ruby is enjoying that water 😀.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really does make you wonder, doesn’t it?

Imagine uncovering that whole theatre, though!

Ruby’s always happy in water 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol, I never knew Wolverhampton had the first set of traffic lights! You live and learn. Lovely photos too! Thanks Jacqueline.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Wolverhampton should get the recognition it deserves!

Wolverhampton Wanderers were also one of the first football clubs in the modern era to have floodlights.

City of Light indeed, but I’m not sure we’ll be going there for our hols.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely on my list! I have a friend who lived here and loved it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lucky friend! What a sensational place to live. It really has everything.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That Evliya Çelebi sure got around! When I was in Istanbul (looking for a public toilet) I stumbled across a mosque associated with the dream he had that sent him out on his travelling and writing journey. What a find that was!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a find indeed!

I LOVE discovering random things like that. It’s what makes travel so special.

I shall have to seek that out if we ever get to Istanbul.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think it’s what made travel special to Çelebi too. The mosque is a bit out of the way, and there’s not too much to see. I chose to walk along the banks of the Golden Horn from old Constantinople to Balat – a route that sounds a lot more poetically beautiful than it actually was! In fact, I was walking through a fairly dismal urban wasteland for most of the way.

I’ve just searched to find my Facebook photo of that day – but fair warning, it is a terribly sad post. It was the first time I typed the words that I would eventually work into the dedication for my book.

LikeLike

Niiiiiiiiice! The travel bug is biting my feet now again. Thanks for another inspiring post 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oooh, we like to induce the travel bug to bite with inspiration…!

That’s what we’re here for.

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person