As we wound up hairpins to Krujë, Mark said, “I wasn’t expecting it to be like this!”

It could be his catch phrase, although I am not sure how he thought Krujë, a town whose handle is ‘The City Beyond the Sky’ would not be uphill. Still, it meant we didn’t need to worry about The Beast’s brakes overheating. At least not until the way down.

Our planned Park4Night stopover was a no go. When we arrived, it was clear we would not get the truck in through a narrow entrance or over a not very sturdy-looking cover that bridged a drainage ditch. As we orbited the city centre in an attempt to find Plan B, Camping Krujë, we happened upon a large car park for lorries and coaches, which had its own Lavazh – the ever-ubiquitous Albanian car wash.

In Britain, there’s a saying, ‘Fur coat and no knickers’. The Albanian version might be ‘Nice car, no knickers’, since, in one of Europe’s poorest countries, we found the number of very swish motors striking.

Despite the prevalence of dusty roads, you never see a dirty car in Albania. Albanians seem very proud of their wheels, and there is literally a Lavazh wherever you look. Usually, there are several on a single street, often next door or opposite each other!

We pulled into the parking lot to contemplate our options. Although Camping Krujë had great reviews and was just down the hill, Mark said,

“I don’t really want to go back downhill after coming all this way up.”

The hill also looked very narrow.

A chap wearing stained navy-blue overalls appeared from the Lavazh and said we could stay for €5 per night. It was not the most salubrious stopover. Certainly, it was the first that required us to manoeuvre around an inspection pit, then stop before we reversed off the edge of the concrete down a precipice. Yet, the vista of a true tequila sunset over the distant hills and Aegean was breathtaking.

We were not in the posh end of town. To walk into Krujë, we had to run the gauntlet of the site’s three-legged guard dog and his sidekick. Both dogs were large, loud, and intimidating, so we were wary, but we soon discovered that if we shooed them away, they were all fur coat and no knickers.

Our primary destination was the town’s famous Old Bazaar, where local crafts and antiques spilled from the doors of dark shop fronts into the narrow streets. Burnished by generations of shoppers, the egg-shaped rock cobbles had assumed the silvery sheen of a London pavement slick with late-November rain. The shops’ gabled wooden roofs almost shut out the sky where they nearly met in the middle. Yet, since the entire arcade was festooned with colourful woven rugs, clothing, and embroidered linen, the overwhelming sense was a carnival of brightness.

On our way into town, we passed the monument to Gjergj Kastrioti, Albania’s national hero.

Better known as Skënderbej or Skanderbeg, the statue depicts him sitting proudly upon a spirited horse. I loved the fact that he did not hold his sword aloft in triumph, like some wishy washy British noble who’d never even been blooded in a hunt. In keeping with his nature, he holds his scimitar by his side. Ready to slash.

For many centuries after his birth in 1405, Skanderbeg was lauded throughout Western Europe. You’ve probably never heard of him, even though you’ll find his statue in Rome, Geneva, Brussels, and London. He is sometimes called ‘Albania’s Braveheart’, since he sought freedom and unity. Others call him the Dragon of Albania, for reasons I shall now explain.

Tiny Albania was sandwiched between the mighty Ottoman and Venetian empires. Sultan Murad II took to heart the wisdom attributed to Sun Tzu and his Art of War: ‘Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer’. As was common at the time, he held Gjergj, son of Albanian noble Gjon Kastrioti, in his court as a political hostage.

Young Gjergj did well. He converted from Christianity to Islam, learned military skills, and rose to the rank of bey or beğ, which means ‘Lord’ or ‘Chieftain’. His campaigns against the Christian world were so successful that his father, Gjon, was forced to apologise to the Venetian Senate for his son’s exploits. The Ottoman court admired Gjergj so much, they renamed him Iskender, after Alexander the Great. And that is how the warlord Iskender beğ, or Skënderbej in Albanian, came into being.

What happened next involved a few errors of judgement.

In an uprising against the Ottoman Turks, Skanderbeg’s father sided with the Venetians, thinking it was his best chance of security. He called his son home to participate in the rebellion, but Skanderbeg remained loyal to the Sultan. The Ottomans won, exiled Gjon Kastrioti, and confiscated his lands.

The Sultan treated Skanderbeg like a son. His popularity at court and military prowess protected him from his dad’s disloyalty to the Ottoman cause. Even so, the second error of judgement came when Skanderbeg asked the Sultan for lordship of his ancestral lands.

Not only did the Sultan refuse, he distributed the Kastrioti land among others. He made Hizir bey governor of Krujë, and gave André Karlo a cluster of villages that were even noted in the records as ‘Gjon’s Villages’.

Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned, but denying Skanderbeg his birthright has got to come close.

Born six hundred years before Lyndon B. Johnson, the Sultan missed out on the wisdom that it’s better to have your enemies inside the tent pissing out, rather than vice versa. For the next quarter of a century, refusing Skanderbeg invited a torrent of effluent to surge between Murad II’s guy ropes.

At the battle of Niš in Serbia, with no father or lands to keep him loyal, Skanderbeg decided, “Bugger this for a game of soldiers,” and deserted the Sultan’s army, which was defeated.

Skanderbeg forced a scribe to forge a letter from the Sultan that named him Governor of Krujë. Then, he abandoned both the Ottomans and Islam. He marched a small army of fellow Albanian deserters home and raised his family standard above the city. You might recognise it. The black double-headed eagle with a red background looks rather similar to today’s Albanian flag.

Image: Skenderbeg Albanian National Hero’ stamp, 2018, Albania Post. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Skanderbeg’s helmet, surmounted with a goat’s head, is held in the Kunthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria. You will see it all over Albania, not least as the logo for the giggle-worthy Kastrati petrol stations. It may represent the ram’s horns symbol of Zeus, worn by Alexander The Great, or that goats were revered as mascots by Skanderbeg’s men, who used their intimate knowledege of the mountainous terrain in their guerrilla campaigns. There is also a legend that Skanderbeg tied flaming torches to goats as a ruse to confuse then outflank his enemy forces.

From his mountain stronghold, Skanderbeg deployed his outstanding military expertise not only to reclaim his father’s land, but to expel the Ottomans from Albania.

Like Genghis Khan, Skanderbeg was a skilled and charismatic statesman. In 1444, he united Albania’s chieftains and their armies under his command. Known as the League of Lezhë, this was the first time that Albania’s disparate tribes were unified under a single leader.

Then, this former Muslim transformed himself into a Christian Superhero throughout Europe by promising Venice that he would keep the ‘Muslim Hordes’ at bay. His baptism back into Christianity was so complete that legend states he took a leaf out of another dragon’s book – Vlad Dracul – and impaled those Ottoman soldiers who refused to convert.

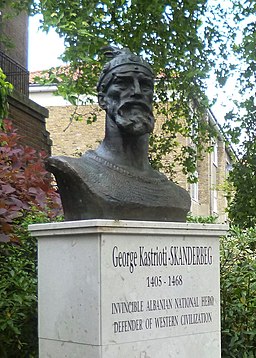

Almost instantly, he captured many Ottoman fortresses in Albania, and gained fame and notoriety for defeating much larger forces through the cunning use of tactics. Pope Calixtus III funded his Albanian campaigns and named him Captain General of the Holy See. An inscription beneath a bust of Skanderbeg in Bayswater, London, describes him as ‘The Defender of Western Civilisation’, and Lord Byron, Edmund Spenser, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote poetry about him. Yet today, outside the Balkans, he is barely remembered.

Image Des Blenkinsopp: Wikimedia Commons Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0

Murad II, the Sultan of Swing, did ask Skanderbeg to return to the Ottoman cause, but he refused. As a mark of his success against them, the Ottomans named him “hain Iskander” – treacherous Iskander”.

Between 1444 and his death from malaria in Lezhë in 1468, The Dragon of Albania successfully repelled every Turkish invasion.

Sadly, Skanderbeg’s legacy did not endure. Within ten years of his death, Krujë fell. After that, Albania remained under Turkish control for almost half a millennium, until the successful Albanian Revolt of 1912, which sparked the first Balkan war. On 28th November 1912, Ismail Qemali, who became Albania’s first prime minister, waved Skanderbeg’s flag from the balcony of the Assembly of Vlor

Sadly, Skanderbeg’s legacy did not endure. Within ten years of his death, Krujë fell. After that, Albania remained under Turkish control for almost half a millennium, until the successful Albanian Revolt of 1912, which sparked the first Balkan war. On 28th November 1912, Ismail Qemali, who became Albania’s first prime minister, waved Skanderbeg’s flag from the balcony of the Assembly of Vlorë. The Conference of London in 1913 recognised Albanian independence, but their re-drawing the borders left almost half of ethnic Albanians outside of Albania. An act which helped to set the scene for the second Balkan war.

Unfortunately, this is a story repeated around the world, where Europeans drew random lines on maps that cut through cultural, religious, and ethnic communities and sowed the seed for many of today’s conflicts.

‘Land of Albania! Where Iskander rose;

Theme of the young, and beacon of the wise,’

Lord Byron, 1812

It was getting late, so we didn’t walk up to the castle, although we usually prefer to view the majesty of castles from the outside. Skanderbeg’s fortress certainly had a commanding position on a bluff, with sheer mountains behind and a view across the whole plain to the coast.

As we strolled back towards our park up, a restaurant owner came out to greet The Pawsome Foursome. He held his hands over his left breast and said,

“Dogs are my heart!”

He told me several times in German that he had a Chow with “Ein großer Kopf” – A big head.

We accepted his invitation to sit on his terrace to enjoy a cold beer with a view of the castle. He brought his Chow to meet us. A large chestnut ball of fluff, I had to concur that he certainly had, “Ein großer Kopf”.

“I use him to hunt birds,” the man said.

I had noticed a small finch singing in a bell-shaped cage outside the restaurant, and wondered whether he used it as bait to lure other songbirds to their death. This was a practice we’d first seen in Urbino, Italy, where songbirds are a culinary delicacy. Almost every home had a small caged bird hung by the door.

Sadly, a cacophony of barking from The Fab Four curtailed our meeting with Mr. Big Head.

Although it was Sunday, our lifestyle can make every day a weekend and we try to control our alcohol intake. We had our regulation two Tirana beers, but then the owner brought out complementary glasses of home-distilled raki.

“It’s made from the grapes in my garden, just down there.” He pointed to a little patch of green, just beneath the terrace.

His menu of homemade food tempted us, particularly since we still hadn’t done any shoppoing. The previous evening, we’d been forced to eat peanuts for tea. Back at the truck, only banana sandwiches beckoned. Unfortunately, Albania is very much a cash only society and we didn’t have enough with us to buy dinner. We’d already tried the only local ATM, but it wouldn’t accept our card.

Despite the banana sandwiches, it’s moments like these that make travelling so special.

Sunday night, on a restaurant terrace, with a cold beer, overlooking a striking medieval castle and a peachy sunset spreading over the Aegean.

As Sun Tzu might have said, “Opportunities multiply as they are seized.”

Join us next time as we seek out a legend in Shkodër.

Ah, I felt like I was in that Bazaar! And what a sunset! That story of Skanderbeg was very Game if Thrones, even included a dragon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know!

There are certain characters from history I would love to meet, or know more about. Now I’ve ”met” him, Skanderbeg is definitely on the list.

Ghengis is another particular favourite of mine. One of the reasons I want to go to Mongolia, of course. I’ve always fancied myself as a Mongolian horse archer! I so enjoyed Conn Iggulden’s series about Ghengis, and the film Mongol is one of my faves. Unfortunately, they never made the follow ups!

LikeLike

I think it depends which side of history you are on as to whether or not you would enjoy meeting these characters!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another place with an amazing history that I’ve never heard of. And what an amazing setting for the town and the castle!! Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is rather fabulous, isn’t it? It’s sometimes called The Adriatic Balcony!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great history and great photos. Love that sunset!

LikeLike

Thank you for recounting the history of the region. You do it well. I always find it fascinating. What an adventure!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Before I visited, I knew nothing about the twists and turns that make Albania what it is today. I find unravelling the history so fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow that is so well said about European countries drawing lines on maps that sewed seeds for today’s conflicts. So true in so many parts of the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfortunately, it is 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person