Our second medieval village of the day could not have been more different. If Sévérac felt organic and quietly lived in, Cordes-sur-Ciel was its theatrical opposite.

From a distance, it looked magical – a town suspended above the landscape, poised between earth and sky on a rocky ridge 328 ft (100 m) above the Cérou River valley. It isn’t hard to see why this part of southwest France is sometimes called La Toscane Occitane – Occitan Tuscany. Rolling hills topped with honeyed stone villages, pencil-thin Cyprus trees – and that soft southern light, so beloved of artists, that seems to flatter everything it touches.

Cordes lies so high above the river that clouds frequently pool below it, especially in spring and autumn, creating the illusion that the village floats above the sky. For centuries, locals knew it simply as Cordes, from the word corte, meaning ‘rocky heights’. It was the poet Jeanne Ramel-Cals, who fled there from German-occupied Paris in 1940, who referred to her adopted home as Cordes-sur-Ciel – a more lyrical reflection of its position above the clouds. She attracted other artists and founded the Académie de Cordes. In 1993, in her honour, the mayor made the heavenly handle she’d coined official.

Image by Sue Harris from Pixabay

As we approached, though, the spell fractured slightly. On the outskirts, we met commerce in the form of gaudy souvenir shops, milling crowds, and a packed shelter for the tourist train. After a brutally hot two-and-a-half-hour drive, poor Rosie lay belly-up in protest. I had tried to keep the pups cool by spraying them with water and had rigged a makeshift sunshade in the cab by wedging a blanket between the sunroof and dashboard in a way that still allowed the fan to circulate air. And like an air hostess, I offered a regular drinks service, passing around the dog bowl – but this is the curse of heading south. You’re always driving straight into the sun.

The Aveyron region boasts over a hundred châteaux, so when we hit the road from Sévérac, it came as a surprise that within ten minutes I’d seen more men relieving themselves than castles – and I’d already clocked a brace of castles. I suppose it is France.

The motorhome aire beneath Cordes cost a modest €8. Mark was reluctant to go up at all. “It’s too commercial,” he said. But it seemed a shame not to, since we were there. We waited until late afternoon in the hope it might cool down.

It didn’t.

Mark delegated navigation duties to me, which was a shock after the shenanigans in Sévérac. I deployed Google Maps, which promptly led us straight up the main road, complete with traffic.

“Have you set it to walk?” he asked.

Before I could even say, “Yes,” he veered off up a narrow, cobbled street marked No Entry to vehicles, and once again, we enjoyed a completely unconventional tour. The shaded alley, scented with moss, was blissfully quiet.

Eventually, our simple strategy of up delivered us to the heart of the town.

Raimond VII, Count of Toulouse, founded Cordes as the first of the planned bastide towns in the aftermath of the Albigensian Crusade. (For more info on the bastide towns, see my post Languedoc, France: The Land That Says Yes! With Wind, Wine, & Rebellion.) It was built between 1222 and 1229 to house the people displaced by Simon de Montfort’s burning of the nearby village of Saint-Marcel. Cordes was both refuge and statement: a fortified settlement offering order, protection, and a fresh start in a region still reeling from religious violence. Although Raimond VII was not a Cathar himself, he tolerated what the Catholic church called heresy, and Cordes rose from that uneasy compromise.

Today it’s nicknamed ‘The City of a Hundred Ogives’, (an ogive is a pointed arch) thanks to its extraordinary concentration of Gothic buildings – whose sumptuous architecture underlines how prosperous it once was. Beneath the market hall lies a well plunging a hundred metres into the rock, a reminder that survival in these celestial heights depended on engineering as much as faith.

“There’s probably a nice view there,” I said, spotting a large square right on the ramparts.

There was – and a very welcome breeze. In the shade of the vast old chestnut trees, next to a 15 ft (5 m) sculpture of a unicorn being ridden by the mermaid queen, we gazed out over the Tarn’s rolling patchwork infinity.

A man with a Border Collie came over. “This looks like a lovely group of British dogs!” he said. “I’m from London, but live near Barcelona.” As we chatted, his three children made me smile – they were stuffing conkers into the viewing telescope, then using it as a makeshift cannon to empty them out over each other – and Mum. He was very interested in our travelling lifestyle, and we had a wonderful discussion about travel, dogs, life, and aspirations. It was one of those easy, fleeting encounters so often gifted to you by travel when you least expect it.

When he visited in 1954, the beauty of Cordes captured the heart of Albert Camus, the French-Algerian philosopher, playwright, novelist and Nobel laureate. I wondered whether we’d found the very location that inspired him to reflect that a traveller gazing out from the terraces of Cordes at night knows they need go no further.

Absurdism lay at the heart of Camus’ thinking. The absurd, he argued, is the tension between our craving for order and meaning in a universe that offers none. His answer is not despair – but defiance. If the world supplies no meaning, we invent it.

If you have read my latest book, More Manchester Than Mongolia, you will already know my amused admiration for Tony Wilson – founder of Factory Records and Manchester’s famous Haçienda nightclub. An unlikely guide to life’s big questions – but Wilson’s advice aligns perfectly with Camus’ philosophy, and finally made the meaning of life click for me. “Choose an arbitrary purpose and stick to it,” Wilson said.

We chose ours – travel – and are sticking to it very happily!

Perhaps that’s all the meaning life ever offers: no pre-destiny or sudden grand revelation – merely a smörgåsbord of whimsical directions one can choose to pursue.

Cordes itself has followed that rule. It has a long history of reinvention – each time selecting a new and diverse path. Conceived as a medieval stronghold, it survived not only the Albigensian Crusade, but the Inquisition, the Anglo-French Hundred Years War, and the French Wars of Religion. When the Canal du Midi connected the Atlantic with the Mediterranean in the late 1600s, trade shifted to water. Cordes became a picturesque backwater – until mechanical looms made it a centre for textiles and embroidery in the 1870s.

Cordes claims to be the first place to stitch the famous Lacoste crocodile, a logo that reflects tennis ace René Lacoste’s nickname, which came about because of his tenacity on the court – and a wager involving a crocodile-skin suitcase. In the late 1930s, when the looms fell silent, the town rose again during the Second World War as artists and craftsmen gathered there around the painter Yves Brayer and poet Jeanne Ramel-Cals. They breathed new life into a place that might otherwise have slipped quietly into ruin.

As the shops closed and the crowds dispersed, we finally experienced the quieter side of Cordes. A golden evening let us appreciate its beauty, shaped by conflict, wealth, and resilience.

We wandered back down by the obvious route and reached the campsite in five minutes. Why Google Maps hadn’t shown us that path earlier remains a mystery!

“I’m glad we’ve ‘done’ the town and can just get off in the morning,” Mark said – and I agreed. We slept with all the fans on, accepting that we were now firmly, unmistakably in the south.

Camus regretted not staying longer in Cordes. “That is what makes the enchantment of Cordes,” he wrote. “Everything in it is beautiful, even regret.”

We moved on with no such longing. I was glad we saw Cordes, but equally glad to leave. Perhaps that, too, is a kind of absurdism. We chose our path and committed to it – satisfied with our reluctance to follow the crowds, and wary of borrowing their enthusiasms or assuming that popularity is always a reliable guide to fulfilment.

Although we found the town too touristy for our liking, the surrounding area is beautiful. There is canoeing on the river and several hikes that start from Cordes. We arrived just as everything was closing, but Cordes also has plenty of restaurants.

Did You Miss?

Below are links to the other posts in my Cathar Country series about the Languedoc in Southern France.

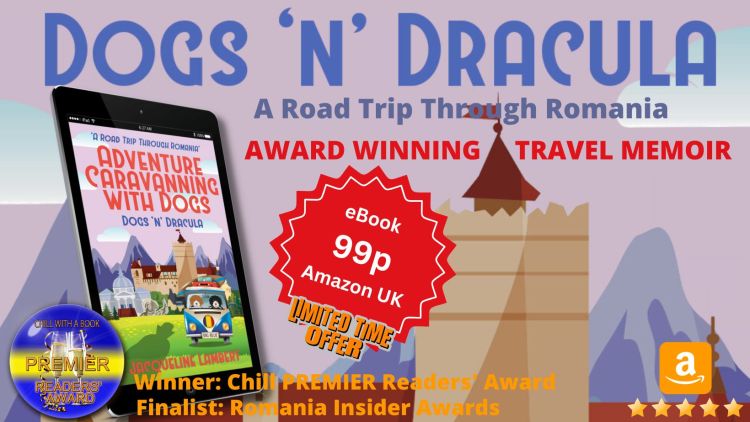

Bargain Book!

Find all my other travel books via the links below:

Enjoy Reading? Never Miss An Update!

Come Truckin’ With Us – Get Outdoors Through Your Inbox!

Image – The Beast at the motorhome aire beneath Cordes-sur-Ciel

A wonderful part of France Jackie and thank you for the tour… spectacular. ♥

LikeLiked by 1 person

My absolute pleasure, Sally.

Thank you so much for reading and commenting – and sharing 🙂 I really appreciate that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooh, I’m enjoying your wonderfully guided mini tours Jackie. What a quaint and fascinating town. That fortress wall reminds me of many cities in Europe that have a walled in part of the city. Luca, Italy is like that. A grand tour indeed. And the serendipity is never knowing who you meet along the way. 🤎🤎

LikeLiked by 1 person

The random encounters are the best thing about travel – although the beautiful places along the way do come a close second 🙂

Despite being a Born Again Italian, I have never been to Luca. We bypassed it because of its popularity, but we must go there one day to see it in the flesh.

Thank you so much for your kind words, Debby, I am so pleased you’re enjoying Lovely Languedoc!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a pleasure to follow Jackie. I am always interested in places other people travel to and what’s discovered there. You do a fantastic job of touring us with you. Hugs xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve captured the charm of Severac and Cordes with your photographs and your historical account of the area. Thanks for the delightful tour, Jackie! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a lovely compliment, Nancy, thank you – and I’m so pleased you enjoyed the tour 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great line ‘assuming that popularity is always a reliable guide to fulfilment.’ It definitely isn’t! Some of our best finds have been as far away from others as you can get. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Glenys! And I agree – it really pays off to get off the beaten track. Not everywhere beautiful has been ‘discovered’!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I must say Cordes looks absolutely gorgeous, so I’m not surprised it’s touristy. Your photos are lovely, and I enjoyed the history, especially the reason it’s ‘sur’ ciel. That part of France is so beautiful, Jackie. I would love to go back there. It’s got so much to offer scenery-wise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose that’s the trouble with being beautiful… 🙂 It was stunning and we have really enjoyed touring south west France. I hope you get back there sometime, Val, but if not, I hope you enjoy travelling along with us vicariously.

Thank you for popping in xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jackie, I shall travel vicariously with you anyway, regardless! 😆

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a beautiful place Jackie I can see why it’s a very popular place to visit. Your photos are stunning. I’m rather enjoying this French trip.

Rebecca x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Rebecca! There’s plenty more to come. It’s a rather special part of La Belle France 🙂

LikeLike